The 1903 Conclave that elected Pope St. Pius X was the scene of an almost-entirely undiscussed historical event – the near election of Cardinal Rampolla as the Vicar of Christ. This forgotten episode of Catholic history should not be lost to history. It contains many valuable lessons.

Who Was Cardinal Rampolla?

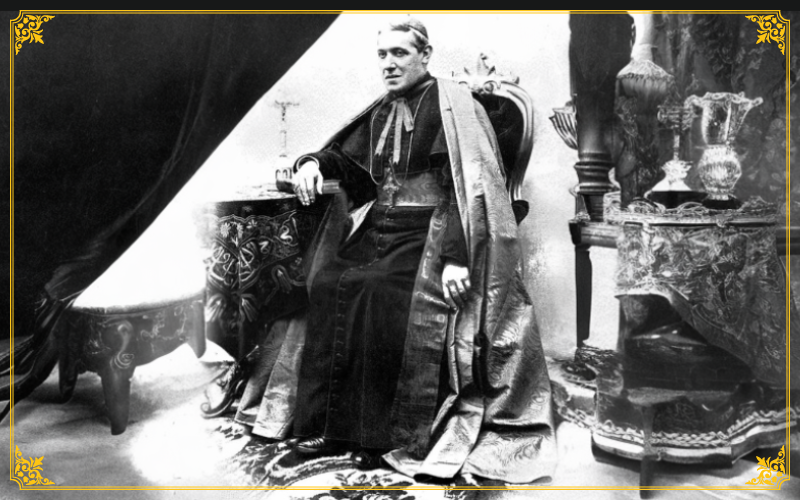

Mariano Rampolla del Tindaro was an Italian Cardinal who served as the Secretary of State under Pope Leo XIII from 1887 until 1903. He was born on August 17, 1843 and lived until December 16, 1913.

Born in Polizzi Generosa, Sicily, Rampolla was ordained a priest in 1866 and entered the diplomatic service of the Holy See in 1877. He became a bishop in 1882 and was appointed the Archbishop of Urbino in 1887. In the same year, he was also appointed as the Secretary of State by Pope Leo XIII, a position he held until the pope’s death in 1903.

As Secretary of State, Rampolla was known for his diplomatic skills and played a significant role in shaping the policies of the Vatican. He was a strong advocate for the Church’s social teachings, including the rights of workers and the poor, and was an important figure in the development of Catholic social thought. It was under Pope Leo XIII that key teachings on the Church’s social teachings (e.g., Rerum Novarum) were promulgated.

The Conclave of 1903

Cardinal Rampolla was the leading candidate for the papacy in the 1903 conclave that followed the death of Pope Leo XIII. However, his candidacy was vetoed by the Holy Roman Emperor Franz Joseph I, who objected to Rampolla’s election.[1] The conclave then elected Guiseppe Sarto, Cardinal of Venice, who took the name Pius X. Today this saintly pope is best known for his conservative policies[2] and his efforts to reform the Church, which included the lowering of the age for Holy Communion and the encouragement for even daily Communions. Despite this setback, Cardinal Rampolla remained an influential figure in the Church until his death in 1913. He was known for his intellect, diplomatic skills, and commitment to social justice.

Why Did Emperor Franz Joseph Reject Cardinal Rampolla?

Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary invoked a power of veto that had not been used in 400 years to eliminate Cardinal Rampolla as a candidate for the papacy in 1903.[3] He did this because Rampolla was known to be a freemason,[4] though the common opinion was that the emperor had been motivated by political reasons related to the conflict between the Vatican and the Italian government at the time. The emperor’s true reason did not become known until 1918.

At the time of the conclave, Italy was in the process of unifying and was seeking to establish its authority over the Papal States, which had been an independent territory under papal rule since 756.[5] The Italian government sought to weaken the power of the Catholic Church in Italy and to assert its control over the appointment of bishops and other Church officials. Cardinal Rampolla was seen as a candidate who would be sympathetic to the Italian government’s position and who would support efforts to reach a compromise with the Italian authorities. This was a concern for the Holy Roman emperor, as Austria-Hungary had traditionally opposed the unification of Italy and had supported the autonomy of the Papal States.

In any event, Franz Joseph I exercised his right of veto, which was a prerogative that certain Catholic monarchs had in the past to block papal elections that they saw as contrary to their interests. The veto power was subsequently abolished the following year by Pope Pius X, who issued a decree called Commissum Nobis, which eliminated the practice of the veto in papal elections. Since then, all papal elections are supposed to be decided by the College of Cardinals without any external interference. As such, it is important to note that the process for choosing a pope has and can be changed.[6]

On What Authority Could Catholic Monarchs Veto Papal Elections?

Catholic monarchs had the power to veto a papal election in the past because they were given a certain level of authority over the Church in their respective territories. The veto power was exercised by Catholic monarchs who were concerned that the new Pope might take positions or make decisions that would be detrimental to their interests or the interests of their countries.

The use of the veto power was rooted in the historical relationship between the Church and the State.[7] In all ancient civilizations, religious and political authority were always understood to have divine origins. Therefore it was natural for religious authorities to have some degree of political power and political leaders to have some degree of religious authority. Within Christendom the Church-State relationship has always been complex, frequently uneasy, and at times down right confrontational. Catholic monarchs saw themselves as the protectors of the Church and believed that they had the right to ensure that the Pope was someone who would work in harmony with their policies. The use of the veto power was formalized by the 17th century and was exercised by several monarchs, including the Holy Roman Emperor, the kings of France, and the kings of Spain, among others.

Praying for a Holy Pope

The next time there is a conclave, we can join our prayers with the Cardinals and pray for the election of a holy supreme pontiff who will restore the glory of the Catholic Faith. For this intention, we can use the Collect prayer for the Election of the Supreme Pontiff which states:

O Lord, with suppliant humility, we entreat Thee, that in Thy boundless mercy Thou wouldst grant the most Holy Roman Church a pontiff, who by his zeal for us, may be pleasing to Thee, and by his good government may be ever honored by Thy people for the glory of Thy name. Through Our Lord Jesus Christ, Thy Son Who with Thee livest and reignest world without end. Amen.

ENDNOTES:

[1] At this moment in European history, what had historically been known as the Holy Roman Empire is commonly referred to by most textbooks as the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

[2] Pope St. Pius X is regarded as a champion by traditionalists for good reasons. There is no doubting his personal sanctity and the motivations that inspired some of his actions (e.g., lowering the age for First Holy Communion and recommending frequent – even daily – reception of Our Lord in Holy Communion). His crusade against modernism and his actions for the liberty of the Church and for the spread of Christ’s reign are certainly praiseworthy.

But we who have the luxury of seeing how history unfolded can observe how this holy pope’s actions in regards to holy days of obligation, fasting, and abstinence were subsequently manipulated to orchestrate a continual sad demise, and eventual complete collapse, of Catholic aesthetic practices. We would do well to keep the practices in force before St. Pius X, which had already been eroded by dispensations and changes for several centuries. At the very least, can we not practice what was decreed by law in 1917?

[3] Since very ancient times, when Church and State worked together in harmony under Christ’s Kingship, the Emperor had received this right of veto over a papal candidate. Similarly, various kings had the right to veto or recommend episcopal consecrations. While this may be unthinkable for us who live in that period of history when Church and State have lamentably been divorced from one another, it was a normal aspect of Church governance and hierarchy within Christendom.

[4] Cardinal Rampolla definitely had Freemasonic sympathies. However, there is historical evidence which suggests that the Emperor received credible intelligence reports that Rampolla was an actual member of the Freemasonic sect. If this seems unbelievable, it should be recalled that electing a freemason to the papacy was long part of the plan of the Carbonari, the most powerful Italian freemasons. To learn more about this we recommend John Vennari’s brief treatise, The Permanent Instruction of the Alta Vendita.

[5] Charles Martel, ruler of the Franks, decisively repulsed the Muslims at Tours in 732. His son, Pepin, defeated the Lombards several times because they were attempting to place the Pope and his lands under their rule. In order to prevent such external pressures affecting the papacy, Pepin gave the Pope these lands in perpetuity. Pepin’s son, Charlemagne, continued to promote the Catholic Faith, made great civilization advances in education, the arts and sciences, and was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day in 800 AD.

[6] St. Peter specifically named his successor. Many of the early popes were elected by the Roman clergy. At times, Byzantine emperors or barbaric kings exercised great influence upon the papal election process. The first papal conclave took place in 1241 after the death of Pope Gregory IX. At that time, there were only fourteen living Cardinals. The Cardinals were locked in a room and were given only bread and water until they elected a new pope. This method was intended to prevent outside interference and to speed up the election process. Over time, the rules and procedures for the papal conclave evolved, and the process became more formalized. Today, the papal conclave is governed by specific rules and procedures set out in the Apostolic Constitution Universi Dominici Gregis, which was issued by Pope John Paul II in 1996 and made 5 key changes:

- The maximum number of Cardinal electors was limited to 120. This was done to prevent the College of Cardinals from becoming too large and unwieldy.

- The waiting period before the start of the conclave was changed from 15 to 20 days. This was done to allow more time for the Cardinals to arrive in Rome and to prepare for the conclave.

- The age limit for Cardinal electors was set at 80 years old. This was done to ensure that the electors were physically and mentally capable of fulfilling their duties during the conclave.

- The voting procedure was changed to a two-thirds majority, rather than a simple majority. This was done to ensure that the new pope had a broad base of support among the Cardinals and to prevent a minority faction from electing a pope against the wishes of the majority.

- The use of any form of audio or visual recording devices, as well as any kind of communication with the outside world, was strictly prohibited during the conclave.

[7] It should be recalled that the Great Persecutions were ended by Constantine, the Roman Emperor, and it was he who called the First Ecumenical Council at Nicea (325 AD), with the approval of Pope St. Sylvester and his legate, St. Hosius of Cordova. Constantine granted the Church buildings and lands, and gave the Pope certain rights and dignities. Emperor Theodosius I called the Council of Constantinople (381 AD) with the approval of Pope St. Damasus and decreed the Catholic Faith to be the official religion of the State. When Rome suffered from weak political power, and barbarians threatened, it was the Pope who shouldered the responsibility of caring for the State and the people’s temporal welfare. The various Byzantine emperors, Frankish monarchs, and Christian rulers continued working with the Pope and his representatives (e.g., St. Patrick and the lords of Ireland, St. Augustine of Canterbury and the Anglo-Saxon kings, St. Isidore of Seville and the Vandal rulers of Spain). This tradition naturally translated to the monarchies of Europe.