Catholic Apologetics #50

(Read Part 2 – Catholic Perspective on the Anglican Revolt)

While many know that King Henry VIII broke away from the Catholic Church and that he is known for murdering and replacing a series of wives, few know the full history of Catholicism in England. After King Henry VIII’s death, after a brief experiment with Protestantism under his son Edward VI who ruled at a young age mainly through regents, Catholicism returned to England under his elder daughter Mary I (1555-1558). But after her reign ended, England officially adopted Anglicanism in 1559 under his younger daughter Elizabeth I (1558-1603). Except during the reign of the Catholic James II (1685-1688), Catholicism remained illegal for the next 232 years until the Catholic Mass could be legally celebrated again in 1791. Yet most Catholics could not hold any public office and had few civil rights. It took the Emancipation Act of 1829 to restore most civil rights to Catholics in England.

How did Anglicanism take over England, a land traditionally called “Our Lady’s Dowry,” and home to so many saints beforehand? Here is a short account of the events that transpired in what is often called the “English Reformation” but should more aptly be known as the “Anglican Revolt against God and Right Order.”

OCTOBER 1517: MARTIN LUTHER NAILS HIS 95 THESES TO THE DOOR OF THE CHURCH AT WITTENBURG

Contrary to popular opinion, Martin Luther was not a pious reformer who embarked upon a crusade to rid the Church of corruption and return Her to a fondly imagined pristine state. Whilst he might have commenced his public career under the guise of a reformer, he ended up a rebel who set into motion a social and religious revolution which rent the Catholic world permanently asunder.

Luther began his revolution in October 1517 by defiantly nailing 95 theses to the door of the church at Wittenburg, one of his main grievances being the practice of selling Indulgences. The Church already knew that the unfettered commerce in Indulgences was sacrilegious, and as such She had never once given Her assent to the unfortunate practice. Remarkably, Luther later feigned complete ignorance, saying ‘As truly as Our Lord Jesus Christ has redeemed me I did not know what an Indulgence was.’ (O’Hare, Patrick, The Facts About Luther, p. 77)

Instead of suggesting any practical solutions on how to reform the Church, Luther offered a collection of fantastical ideas which he attempted to pass off as being theologically sound. For example, in No. 24 he writes that ‘Christians must be taught to cherish excommunications rather than fear them’ whilst in No. 25, he states that ‘the Roman Pontiff, the successor of Peter, is not the vicar of Christ over all the churches of the entire world, instituted by Christ Himself in blessed Peter.’ Luther proposes in theses 31 and 32 that ‘in every good work the just man sins’ and ‘a good work done very well is a venial sin’. Finally, he proposes in No. 38 that ‘the souls in purgatory are not sure of their salvation, at least not all…’ These theses were sent to a board of distinguished professors, who Luther called ‘buffoons and earthworms.’ In short, 41 of the 95 were condemned as heretical by Pope Leo X in the Bull Exsurge Domine on June 15, 1520.

This was, however, too little too late. Luther appeared at a time when the Church was in desperate need of genuine reform. Many of the higher clergy were more interested in holding onto political power and things of this world than exercising their pastoral duties. The souls of the faithful were being neglected. Bishops and Abbots were comporting themselves more like princes than priests. The faithful had become superstitious, immoral or indifferent. The Papacy had lost its authority, and Rome had become infected by the spirit of paganism. Princes and governments had set themselves up against the Church.

This was a revolution waiting to happen. Indeed by a certain measure, Luther’s doctrines spread with greater rapidity than Christ’s own. When the last of the Apostles died, Christians were still hiding in the catacombs in fear of their lives. When Luther died, Protestantism in its many forms had spread like wildfire from Germany to Switzerland, up to Norway and Denmark and Sweden, down to France, Hungary, Poland and the Netherlands, and finally to England. God, it appears, in His Infinite Wisdom, had allowed this revolution to happen. The question is this: Would we have had the true and Catholic reformation – long desired but delayed by so many difficulties, taken up and accomplished by the Council of Trent between 1545 and 1563 – if Luther had been motivated by a genuine desire to see the Church reformed?

NOVEMBER 1534: HENRY VIII’S ACT OF SUCCESSION, USURPATION OF VICAR OF CHRIST AND BEGINNING OF SCHISM

On November 3, 1534, the English Parliament re-assembled to finish off what it had begun earlier that year, which, as the Imperial Ambassador at the time had reported, was ‘to complete the ruin of churches and churchmen.’ Since 1531, Thomas Cromwell had been laying the statutory foundations for the breach with Rome, which in turn prepared the way for the radical religious changes which were implemented during the reign of Henry VIII’s son, Edward VI. During these years, a number of bills authored by Cromwell and designed to weaken the power of the Church and strengthen that of the State were passed in Parliament to the detriment of the kingdom.

Notable amongst Cromwell’s bills were the Act of Restraint of Appeals (1533), the First Act of Succession (1534) and the Treason Act (1534). In the former, all appeals to Rome were abolished and henceforward, the king, rather than the pope, would be the final court of appeal in both ecclesiastical matters and matters of conscience. In the Act of Succession, the yet to be born Princess Elizabeth who was the daughter of Anne Boleyn was made successor to the Crown, whilst Princess Mary, daughter of Catherine of Aragon, was declared illegitimate and therefore deprived of the right of succession.

Cromwell wrote an oath to accompany the Act of Succession, and in April 1534 he sent out commissioners to extricate signatures from members of both Houses of Parliament. Under the Treason Act, anyone who refused to take the oath was subject to a charge of treason which was punishable by the particular gruesome death of hanging, drawing and quartering. It is no surprise that with the exceptions of Sir Thomas More and Bishop John Fisher, all the members of Parliament readily agreed to sign. Later, the king’s commissioners travelled out to administer the oath to the general populace, and even those who were unable to write were required to make some kind of mark on the document.

The Act of Supremacy passed in the middle of November 1534 and it finally effected the breach with Rome and placed the entire English church into schism. Henry’s declaration that he was ‘the only supreme head on earth of the Church of England, called Anglicans Ecclesia’ was an illicit assumption of the headship of the Church and was at complete variance with Catholic tradition and without precedent. As a result, England floundered in a state of schism for nearly two decades until November 1554, when Cardinal Reginald Pole finally landed upon the shores of the kingdom to reconcile her to the Church.

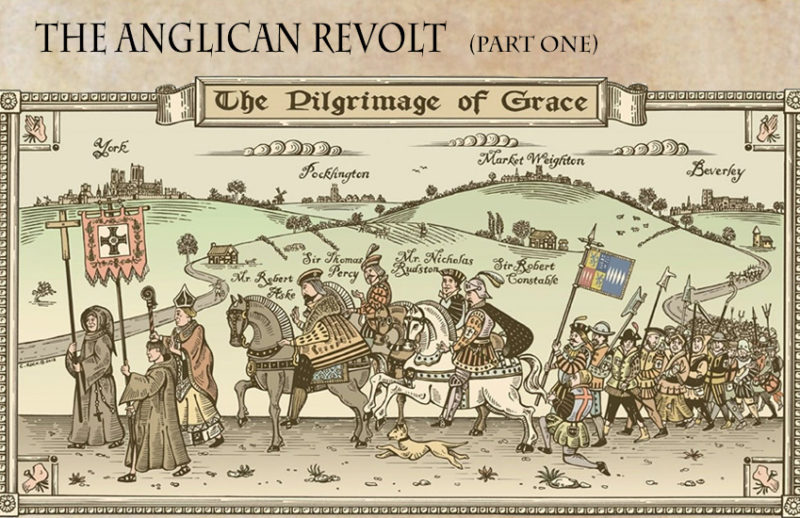

OCTOBER 1536: PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE. CATHOLICS MARCHING UNDER THE BANNER OF THE FIVE WOUNDS IN RESPONSE TO NOVELTIES OF ‘REFORMERS’

On October 13, 1536, Robert Aske, a partially blind barrister from Yorkshire, gathered nine thousand men and marched to York under the banner of the Five Wounds of Christ in response to attacks both upon England’s monasteries and the ancient Faith. In 1534, Thomas Cromwell had already begun to plan the dissolution of England’s monasteries by assessing the total value of all the Church property, which involved handpicking a small group of suitably anti-Catholic individuals and sending them out to investigate the spiritual and temporal conditions of every monastery in the realm. They had just six weeks and managed to visit only one-third of the religious houses on their lists. Still, Cromwell’s spies cobbled together a report of supposed tales of monkish evilness and presented it to Parliament in 1536. In response, the politicians passed the Bill for the Dissolution of the Lesser Monasteries.

Over the next few months, the people watched with growing dismay as King Henry VIII’s agents traveled from monastery to monastery, summoning the monks to appear before them, informing them of their impending doom, expelling them from their homes, and then taking anything that could be put into the back of a cart. After they had left, they sent in workmen to demolish the buildings. Many of the abbots were easily bought, cooperating with the King in their own demise.

In the meantime, Cromwell had appointed the most radical, anti-Catholic preachers he could find and sent them out to openly preach against Catholic doctrine. In August 1536, he issued a set of anti-Catholic Injunctions in which the clergy, under pain of imprisonment, were compelled to obey the legislation which abolished the Pope’s jurisdiction. They were also required to preach the Ten Articles as well as dissuade the faithful from undertaking pilgrimages. The veneration of the Saints and the invocation of their intercession, rejected by the Reformers as unbiblical, was deemed superstitious and prohibited.

By October, the people had had enough. Upon arriving in York, the first thing that Aske did was to expel the King’s squatters from the religious houses and recall the monks and nun to their homes. He then moved to Doncaster with approximately forty thousand men, each man wearing a pilgrim’s badge. Such was the strength and organization of this army that the King was compelled to negotiate with the rebels, promising that a general pardon be granted and that Parliament be held at York within the year to address their issues.

Unfortunately, Aske foolishly believed the King, and told his followers to disarm and disband. It was soon manifestly evident, however, that Henry never had the slightest intention of keeping his disingenuous promises. In 1537, Aske and several other leaders, as well as four Abbots, were rounded up, arrested, convicted of treason and brutally executed. Henry declared martial law, taking revenge upon his own subjects by ordering a routine series of massacres, and the north of the country became littered with corpses dangling in chains from gibbets. Henry had killed the opposition. The pilgrimage had failed. By the autumn of 1539, some one-hundred and fifty monasteries had signed their own death warrants and handed over their property to their tyrannical monarch.

Want to read more?

Latest Articles by Matthew Plese