Note: The information in this article is largely based on several chapters in The Three Ages of the Interior Life by the great Dominican scholar, Father Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange.

Why This Topic Matters

St. Thomas Aquinas divides our passions generally into two categories: concupiscible and irascible. Understanding what these are and how we combat each in practice is ultimately geared toward helping us overcome our evil inclinations and thus live a life in greater imitation of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

The Thomistic Theology Page summarizes this purpose well:

“Because the passions are susceptible to becoming disordered, the will needs to be perfected by settled dispositions or habits by which it can direct the passions to appropriate objects (the right thing, at the right time and in the right amount). The habits which dispose one to desire well, i.e., appropriately, are called virtues.”

What Are the Concupiscible and Irascible Appetites?

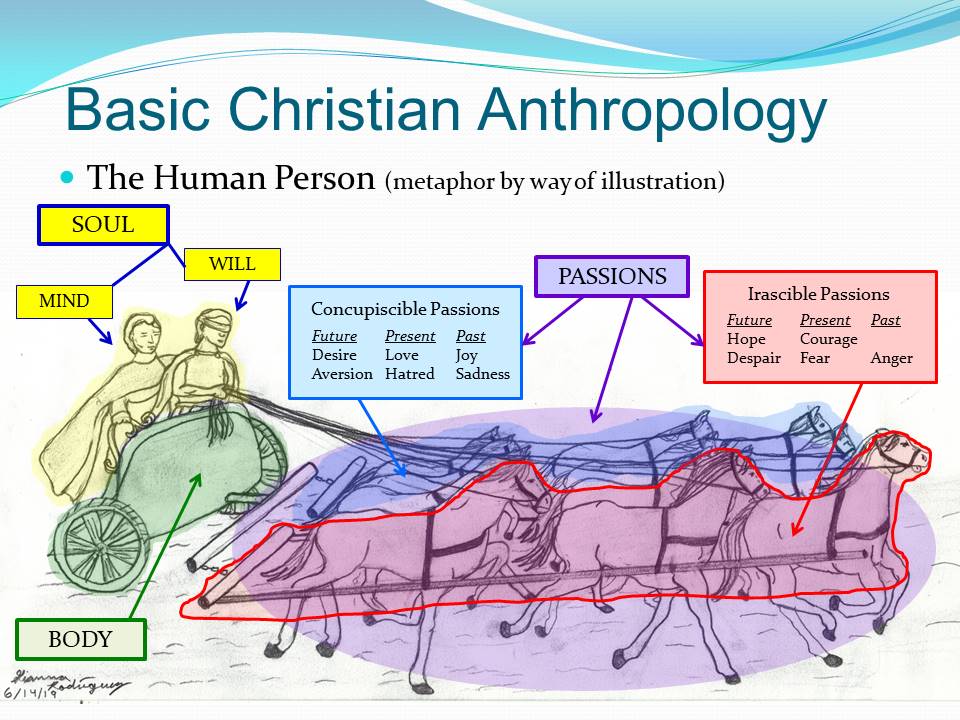

There are two kinds of appetites. First, there are the six concupiscible appetites, which incline a man to seek a sensible good and to flee injury. These appetites are (in terms of attraction towards an object): love for a good in the present, desire for a good in the future, and joy for a good in the past; and their counterparts (in terms of repulsion from an object): hatred for repulsion in the present, aversion for a future repulsion, and sadness for a repulsion in the past.

Secondly, there are the five irascible appetites, which incite a person to resist obstacles and, in spite of them, to obtain a difficult good. These appetites are (in terms of good that is difficult to attain): courage for a difficult good in the present and hope for a difficult good in the future; and their counterparts (in terms of evil that is difficult to avoid): fear for an evil in the present, despair for an evil in the future, and anger for an evil in the past. There is no counterpart for anger because there is no difficult good to attain in the past.

Virtue and Christian Anthropology

It may be helpful here to quickly review fundamental points from our basic catechism. The human mind and human will are both powers of the human soul. They are spiritual realities and do not consist of physical material. The purpose (end) of the mind is to know the truth and the purpose of the will is to choose the good. This means both of them are directed towards God, who is Absolute Truth and Absolute Goodness. The passions, on the other hand, are powers of the body and they do involve a material component (hormones, electrical impulses, etc.).

St. Thomas, following Aristotle, teaches that the passions and emotions are neither good nor bad in and of themselves. In general, these “passions” are powers which humans and animals have in common. As such, they are amoral. However, human behavior is greatly influenced by the passions. Their morality depends on the intention of the will – which animals of course do not have. The act of virtue is even more meritorious when it makes good use of the passions in view of a virtuous end.

The passions must be moderated proportionally to what reason requires for a given end to be reached, given a specific set of circumstances. Thus, the passions must be governed and regulated by the mind exercising right reason. Animals also lack a mind (which is not to be confused with the brain, though the mind and will are intimately and mysteriously related).

Rather than giving way to haste by seeking to please our passion or do our own will, we should conform our will to God and pray for the help of the Holy Ghost. There can be no fruitful interior life without a struggle against self.[1] Fallen man must regulate and discipline his passions so as to cause the light of right reason – and even that of infused faith and Christian prudence – to descend into his sensible appetites.

Active Purification of the Sensible Appetites

Some passions (frequently also called appetites) require direct combat and others require immediate flight from danger. It is important to understand which we should do in any given situation. For instance, unlike sloth, which we can fight by resistance (e.g., resisting the urge to sleep in and miss Sunday Mass, by forcing ourselves out of bed), lust is fought by fleeing from the occasion (e.g., immediately leaving the computer when tempted to look at pornography or quickly turning away at the first glimpse of an immodestly dressed person).

Concerning anger, we see the example of Our Lord, Who taught us to offer our other cheek to those who strike us, as part of His perennial teaching: “love your enemies.” The mortification of the irascible appetites makes us acquire the virtue of meekness. And through meekness, we can conquer ourselves.

Meekness is greatly misunderstood today. It does not mean to be “mousy” or “weak.” Rather, the meek man is able to control his passions and moderate his reaction when he is wronged. Even when insults are hurled at him, he suffers injustice; or when he is calumniated, he is able to offer a response governed by truth and charity. Sadly, our world often sees such a virtue as ‘weakness.’

In truth, the meek man is incredibly strong because he is able to control his own passions. A good analogy is to consider the passions as horses which pull a chariot. The mind and will should drive the chariot instead of allowing the horses to wildly pull the person haphazardly in conflicting and dangerous directions. Those who allow themselves to be governed by their passions may appear ‘strong’ as they fret and rage, but are in fact weak because they are unable to rein in and control their passions. As we develop Christian virtues, including meekness, we habitually discipline our passions and our responses when those passions are aroused.

Grace Builds on Nature

To finish the work of the active purification of these appetites, a more profound purification is needed which comes directly from God (i.e., the passive purification of the senses), which the theologian Father Garrigou-Lagrange covers in much greater detail in his work. We should consistently pray to God for the graces needed to purify our passions.

Jesus, meek and humble of heart,

make my heart like unto Thine

Note: This topic will be continued in a future article which addresses the active purification of the memory and imagination, the intellect, and the will.

END NOTES

[1] “Follow your heart” or “Search your feelings and follow them” is passed off today as popular wisdom. Yet it is a grave error which reduces man to the level of the beasts. With the aid of grace, man is to govern himself by his higher faculties (mind and will), not his lower appetites. This topic was covered more in depth by Mr. David Rodriguez in a talk he gave at a Fatima Center conference in Seattle (June 2019): The Heresy of Emotionalism.